Subconscious Terrains: The Architecture of Resilience

Longitudinal Studies of Spatial Cognition in the Social Ecology of the Periphery

Between a Sword & a Wall

The Quiet Migration: A Portrait of the Migrant Caravan

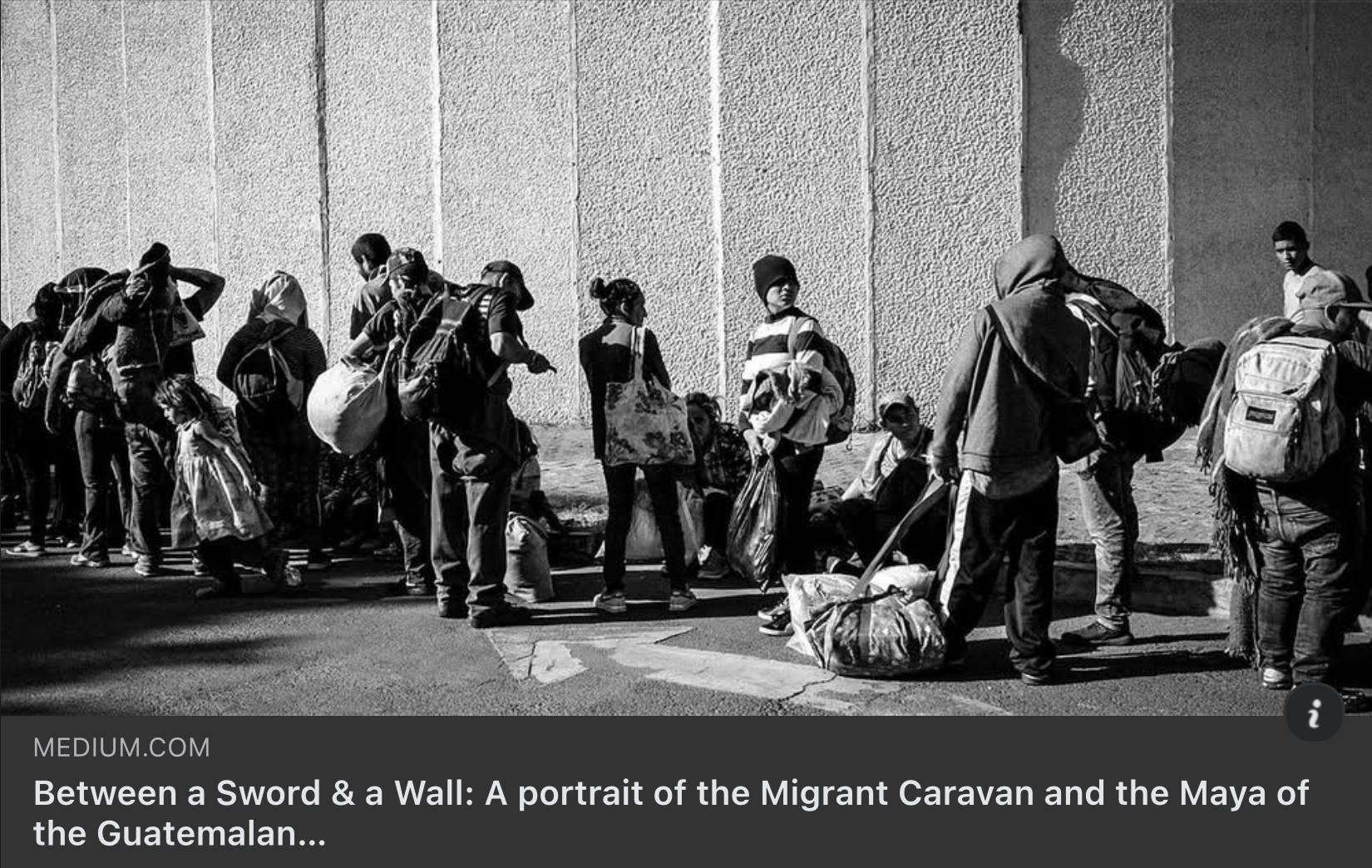

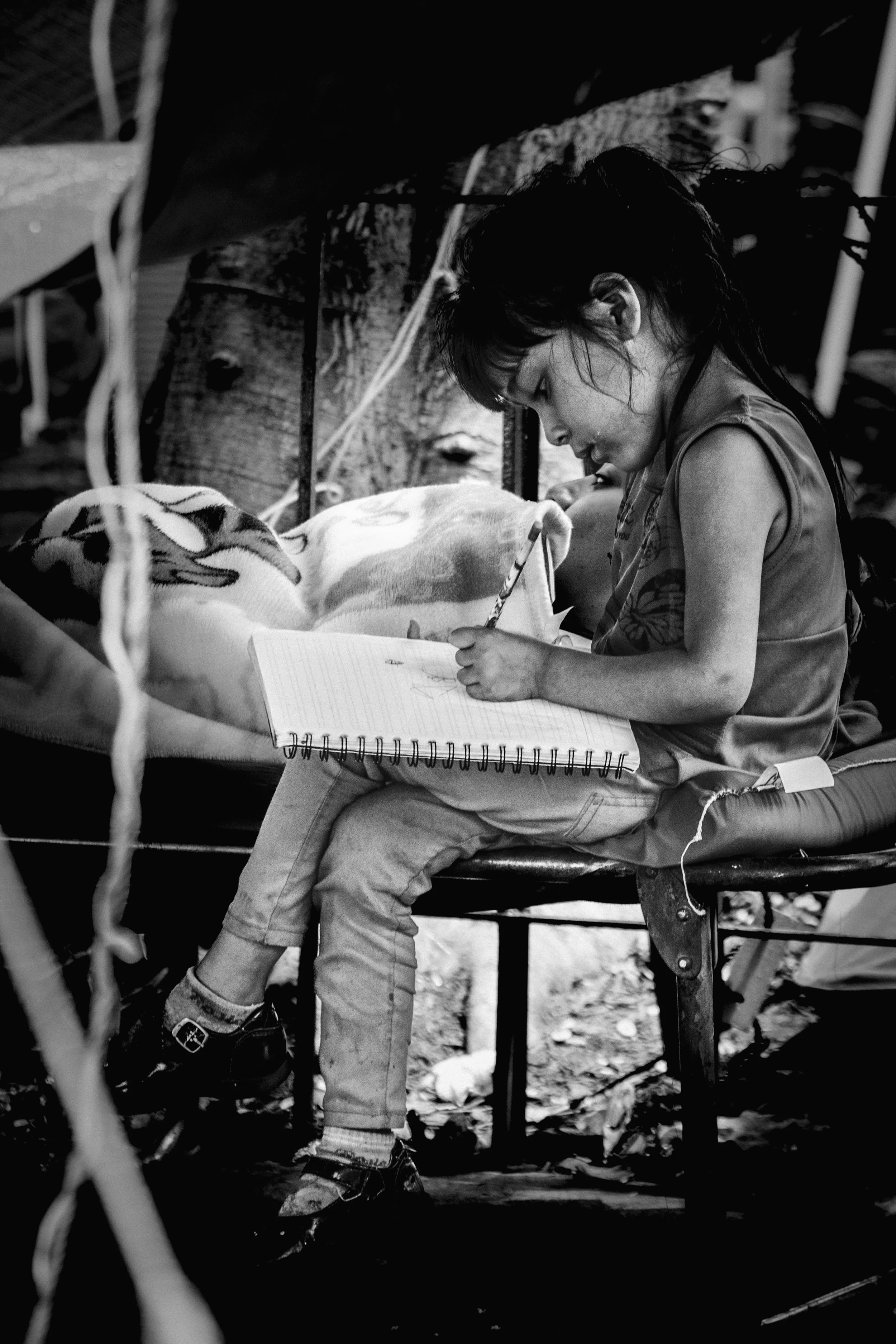

When the first caravan arrived in Mexico City in the fall of 2018, tents had already been pitched in a large football arena. Medical services, a kitchen, consoling, clothing donations, and even a mobile dentist office awaited them. A wrestling ring had been erected at the base of the stands for masked luchadores to body slam one another, bringing temporary joy to the hardened faces of the masses of children waiting their turn to bathe in the plastic sinks set up by the porta-potties, which were usually reserved for concert venues.

I’d already been living in Mexico City for some years, so when I caught word of their arrival, I showed up right on time to see a semi-trailer pull up to the curb. Spilling out of the back, amongst a jam-packed crowd of migrants, I watched in shock as a black- skinned boy tumbled to the street, too weak to stand on his own. He was slow to get up, then collapsed again at the curb, clutching a toy racecar in his reedy arm. I approached, kneeled, and handed him a fistful of snacks I had bought on the way to distribute. I was there to help, not only to take pictures. But as I walked away from the boy and into the migrant camp, I couldn’t keep my eye off the viewfinder, as I felt that no one else would believe what I saw unless they saw it themselves—knowing that only migrants and volunteers were here, not the news, not the press, not a camera—just me, and my own. I was in utter shock, and the camera helped create a barrier between me and the level of human suffering I had never personally witnessed before. The large tents were packed with people; the smell of sickness and weakness filled the air and assaulted my senses, lingering for days. Desperation drained my energy, and I felt dizzy. My heart ached and raced with anxiety, and I did my best to stay calm.

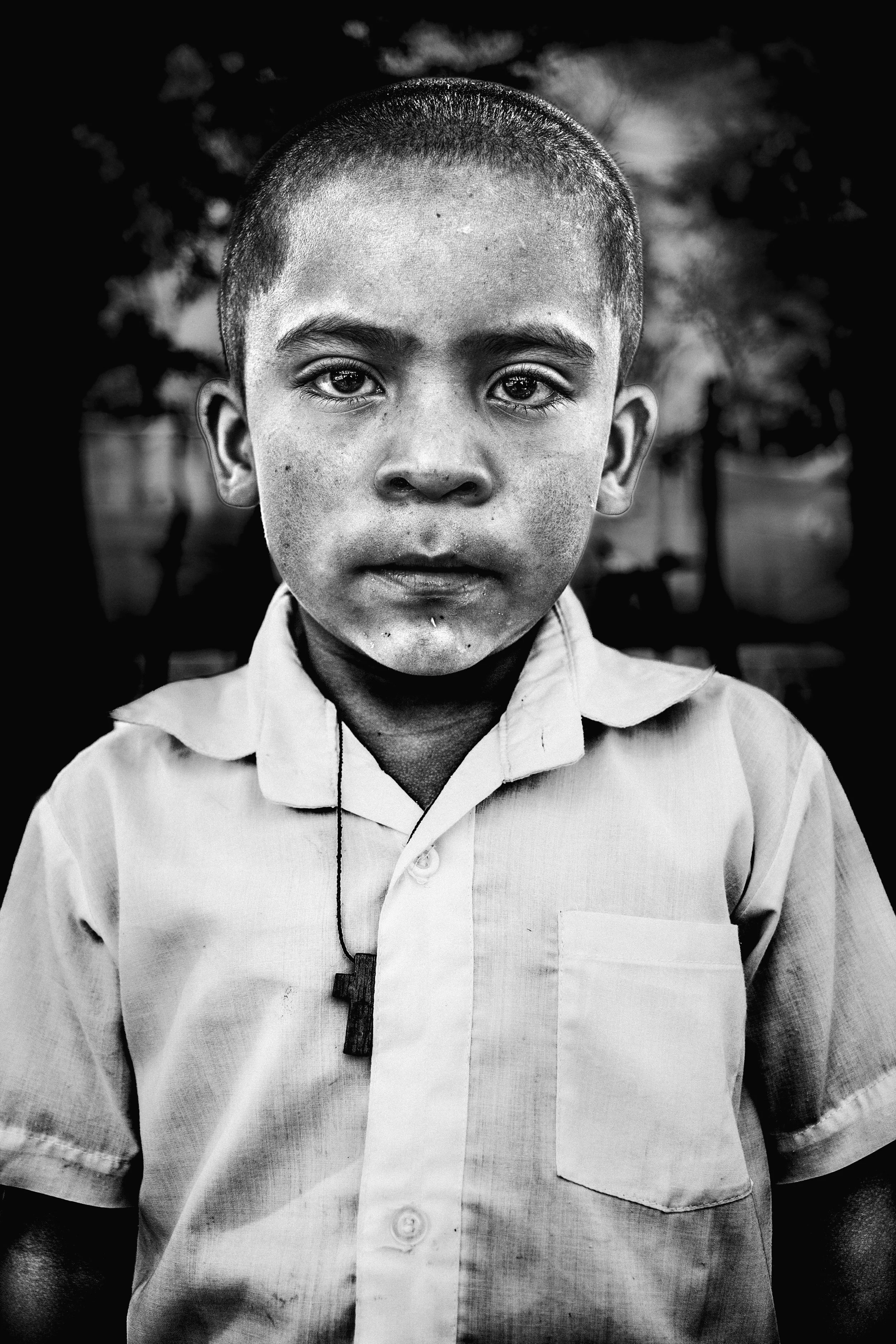

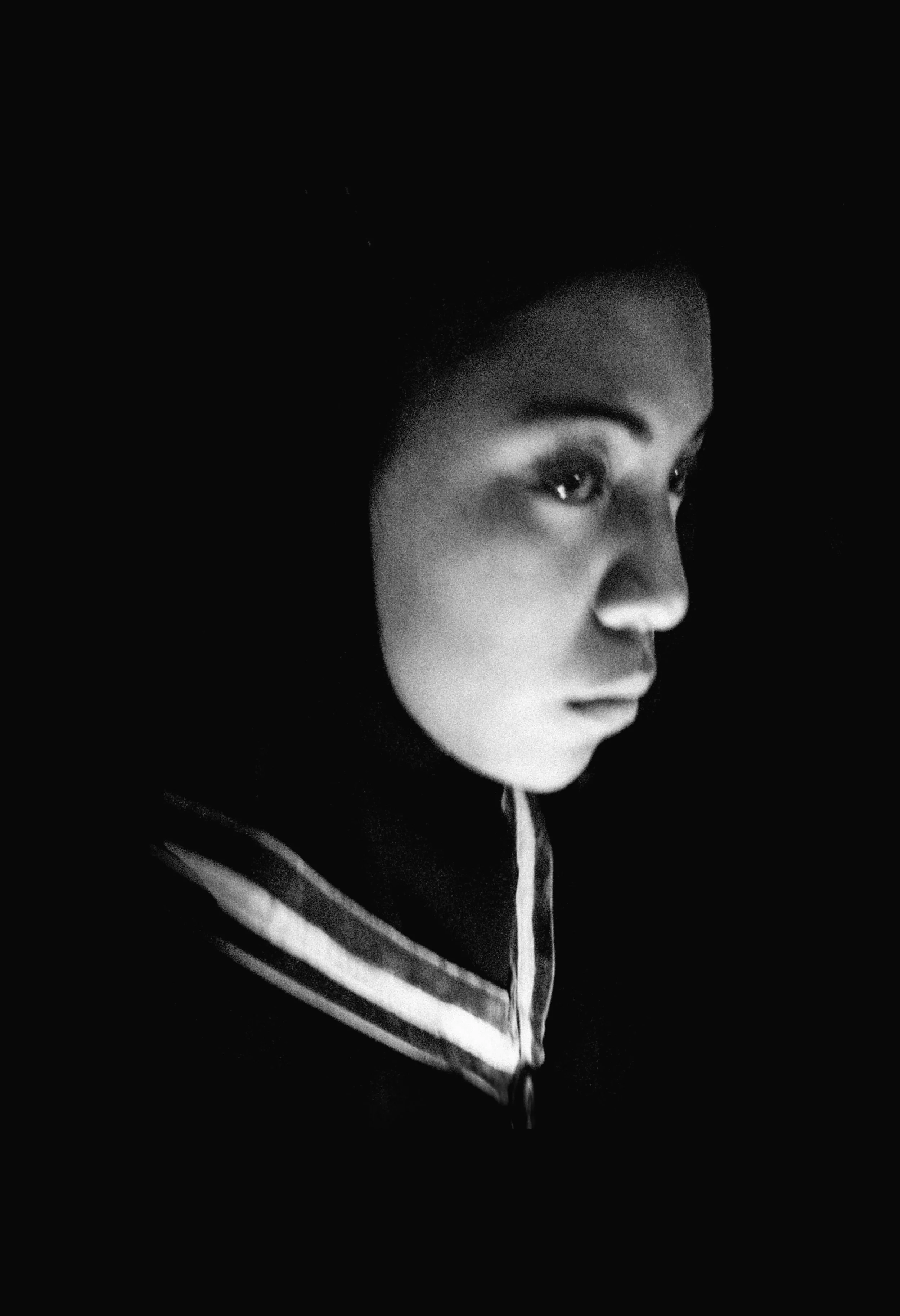

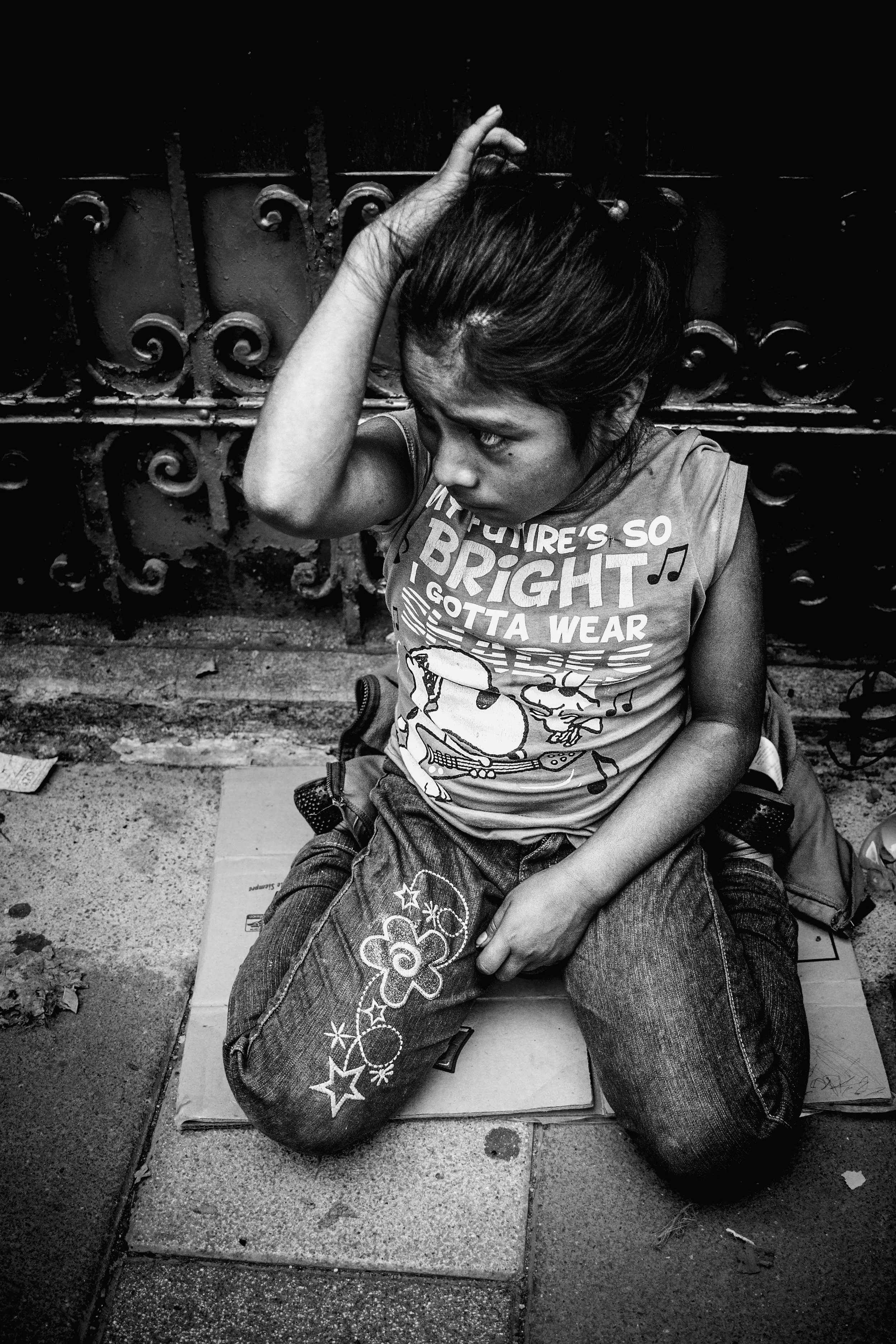

Yet, amid this nightmare, there were smiles. I focused my camera on those faces of joy and hope— young, innocent faces that I felt others needed to see. Among the mothers and fathers, there was determination and hope. What stood out most was that, despite what their children had endured, they played, frolicked in the sun, and watched the luchadores tumbling in the ring with cheers. Children are tough; they can endure. Those are facts, none of which can justify this human tragedy.

I stayed as long as my legs could keep me upright, my body trembling. When the snack bag ran out, I left, determined to return with two large bags the next day. That evening, as I looked through my photos, I couldn’t help but focus on the image of the boy collapsed on the curb, clutching his toy car. There was a look of suffering in his eyes that went beyond any of the others. Of course, everyone looked tired and in pain, but his eyes showed something more severe and urgent. The next day, I was determined to find him. I searched everywhere but couldn’t locate the boy. Finally, after asking around, I learned his name was Johnathan. I went to the medical tent, but the nurses had no record of him. Then I spotted a teenage girl with long, thin braids who looked like she could be his sister, as few of the children there were of African descent. And indeed, she was. She told me Johnathan had been rushed to the hospital that morning.

I left a note with the girl to give to her mother when she returned to the camp. And I went back day after day, but couldn’t find any of the family. Finally, I got a call. It was a woman named Argentina, Johnathan's mother, she explained. I told her I was a photographer and that I had photographed her son the day they arrived. I mentioned that I sensed something was wrong and was worried. She started telling me that he was being treated for an undiagnosed case of diabetes, that he’s been malnourished most of his life, and has trouble maintaining weight. The doctors were doing everything they could to prepare him for the nearly 2000 miles they still had to travel, mostly by foot and hitchhiking, aiming to reach the US border. But he needed medication and to eat healthier, and she was scared and unsure what to do. I told her I wanted to help Johnathan and her family in any way I could, and I didn’t think he’d be able to make the journey in his current condition, especially as they were about to cross Mexico’s most dangerous and rural region, far from hospitals or medical care. She was very cautious about accepting my help. She worried I might want something in return, which was very wise of her. She also shared about the horrors many had faced along the way—rape, and worse, if such a thing exists. Basically, she was worried I might be a human trafficker.

The Mexico City shelter had established a moderate level of security by this point because human traffickers had already started arriving, attempting to lure women away from the shelter's protection. It was a real danger. Here and now. On their way to Mexico City, already, 100- 200 people had been kidnapped by the cartel for purposes such as forced prostitution and human slavery. But eventually, I earned Argentina's trust, and she agreed to let me help her and her family, which included Johnathan, who was 7, and her two daughters, aged 11 and 14. Knowing they would risk so much by going on foot, I insisted on buying tickets for a chartered bus that would take migrants who could afford to pay a high price a ride north. I also purchased a large backpack and filled it with food that I hoped would be suitable for Johnathan’s condition, along with socks, hats, gloves, coats, and a large wool blanket. I saw them off as they boarded the bus. But two days later, I received a call. It was Argentina; they were at the hospital in Guadalajara. Johnathan was sick again and receiving more treatment. After we hung up, I didn’t hear from her again, but I was determined to find them. So, I bought a flight to Tijuana.

I stayed in a hostel full of hippies a block from the border crossing and set out on foot through the redlight district, passing some of the roughest streets in Mexico I’ve ever seen, hoping the crude directions I had to the camp were at least somewhat correct. They were not. But with some blind luck, I stumbled upon it. It was a large area right against the border. There was no organization here. No volunteers. No camp per se. A day earlier, I was told, the city had forced them out of a nearby stadium and locked the gates. Now they are holed up in a maze of muddy streets crammed with tents and the debris of living outside—piles of belongings abandoned when they were chased from the camp and moved 45 miles south of the border by bus. What remains looks like a city dump.

The location to which many had been bused lacked both running water and electricity. It seemed the authorities in Mexico, including the mayor of Tijuana, had come under pressure from the Trump Administration and were trying to break their spirit through exhaustion and hunger, and by distancing them from the border, in what appeared to be a very strategic move. For those refusing to leave, the sight of the border offered hope. Although they were numerous and starving, they were holding strong, waiting for an opportunity to achieve what they had traveled 2,000 miles for: asylum.

Again, I brought large bags of snacks and every apple I could find at the corner stores along the way, along with my camera. I needed the world to see. I recognized many faces and knew many of the children by now, and it was a bit surreal to see them thousands of miles away. I knew the sweet ones and the brats. The polite ones who wanted to share and who would take me to show me where there were more hungry kids. I knew the ones who loved to eat and would beg for more and more. The picky ones who turned up their noses at strange snacks, and the ones who would eat dirt if they had to, and those who were too lost to eat anything at all. But they were all so beautiful, even in their desperation and exhaustion. By then, they knew me. They would run up to me with smiles.

The adults did their best to keep an eye on their kids, but the children seemed more resilient to the lack of food and nourishment than the adults, who looked exhausted. And their kids were stir-crazy, as driven mad by the limbo. I saw very few other sources of food for the families, let alone the ever-hungry kids, and it haunted me to think I was practically their sole source of the apples they cherished most. Apples, apples, apples, or rather... "Manzana, manzana, manzana," they would shout as they ran up to hug me and play with my hair. "Guero, Guero," which means "blonde" with affection. I had seen many mothers picking lice out of their hair, but I didn’t care. They gave me courage. Those kids were the bravest souls I had ever witnessed, and I would miss them. This neighborhood was one of the shadiest I’ve ever seen. But I felt much safer among the migrants than I did among the locals. The migrants were good people, and they treated me well. I was very grateful, and they were very thankful for my support and the fruit I had brought their children. They also enjoy talking and having their photo taken, and I wished them the best, though it was obvious all national and international organizations had now abandoned them.

The following day, I saw two men trying to cram a dead migrant with rigor mortis into the back of a make-shift ambulance too short for his legs, so they shouldered the door again and again, trying to break the lock in his knees. I went into a nearby corner store for more apples and snacks. I cleared the shelves, and on my way out, out of the corner of my eye, I saw a familiar face. It was Johnathan, his two sisters, and Argentina. I was very relieved to see them. I immediately gave them all the food, and I took a group photo of them sitting on the curb. But Johnathan did not smile. I could see he was still very ill. Argentina told me that Johnathen was now sick with bronchitis. I gave her money for her phone and told her to call me every day and keep me updated. She told me where her shelter was, as she was staying in one specifically for women and children. I got up early the next morning and walked to the shelter.

I have been to many sketchy places around the world, but the walk to this shelter was one of the scariest moments in my life, at best, post-apocalyptic. This part of Tijuana, just blocks from the US, felt like a lawless war zone. Mountains of garbage were everywhere, with people sleeping on top and snuggled inside. Drug addicts roamed freely, and the mentally ill fought their demons in broad daylight. As I finally reached the shelter, directly across the street from the border wall, the gate to the shelter was closed and locked, but I was able to peek through a hole in the sheet iron, and I saw a large group of tents and a few picnic tables where a few children were being fed. I knocked, but no one came or even looked my way. Later that day, I got a text from Argentina, and she told me that she had missed her appointment for asylum because she had to take Johnathan back to the hospital. I asked her to please go, even though she was late, and to meet me after. She told me with weary eyes that they had told her she was out of luck in so many words as she clutched onto a handful of prescriptions from the hospital for Johnathan’s bronchitis, Johnathan barely standing at her side, his shoulders hunched, chest caved in.

I took her to a pharmacy and paid for their supplies, while Johnathan lay on the floor, too dizzy and ill to stand. As we left, fortune smiled on us when a group of young immigration lawyers, volunteering their services from San Diego, passed by. We talked with them over lunch, fed the family, and discussed with Argentina and Jonathan the importance of his eating well. But of course, by now, we all understood that the food being provided to them was very poor. The lawyers arranged an appointment with Argentina, and I accompanied her to the address provided later that day. I made sure to emphasize that everyone was deeply concerned about Johnathan’s health and that he urgently needed proper first-world care. They reassured me they would escort the family to the border to apply for asylum the next day.

However, I wasn't surprised when, once again, the USA turned them away. Now, I sat on the curb, trying to think of what more I could do. Despite witnessing this entire ordeal for weeks, I felt like I was only just beginning to understand, as Argentina told me she felt trapped between a sword and a wall. And I believed she was right. But it wasn’t just her. It was Johnathan, and thousands upon thousands—all of humanity, me and you. It is the future. Our future. All of ours. And just as I was losing hope, Argentina told me she was all losing hope. I thought about telling her she could repay me by holding on to hope, but I didn’t have the heart. And I realized, she doesn’t need to repay me. In fact, what I am trying to do is repay her for what my privilege, our privilege, had taken from hers.

That evening, I watched on the television at the hostel as the US Border Patrol shot tear gas canisters at a mother with two young daughters, about 5 and 6 years old, as they made a desperate run for it across a dry riverbed, trying to escape the horrors of Tijuana for the world to see. “An invasion,” the rhetoric would spin. I had become familiar with the girls and had photographed them numerous times, starting back in Mexico City. Gueritas, meaning they had blonde hair, a rare trait for little girls from Honduras, girls who drew broad smiles across their faces when they saw someone like me— someone with hair so similar to theirs—cheering as they held their apples like baby dolls before my lens.

Eventually, after many efforts, my lawyers and I were able to obtain asylum for the family, and I helped them settle into a new life in New Orleans, near the courthouse where her future court date had been assigned. She found assistance and community at a church with a program for migrants, and we kept in touch for months. However, as the pandemic settled in and left our lives turned upside down, we lost contact.

Often, as I read about “Alligator Alcatraz” and the (masked) ICE abduction of migrants, I wonder and worry about Argentina, her family, and especially about Johnathan. But I prefer to imagine him playing soccer with his classmates rather than seeing him behind bars, waiting for a flight back to Honduras or a third-country option like South Sudan, where the first-world healthcare he desperately needs will cease to exist.

"My wish is to be in the U.S. to get Johnathan the treatment he needs; that is my dream,” Argentina once wrote me in a message. “My brother died from untreated anemia, and it hurt me a lot because he had so many dreams. I was with him all the time in the hospital, and now I am doing the same with my son. I don't want Johnathan to go through the same suffering. It worries me because he has gotten sicker and sicker. Last year, he was in a coma for a month. I want so badly to have control over his mealtimes, but when I go in search of food, there is often nothing. It has not been easy on Johnathan, and that scares me to death. I wish I could have a place of my own and to be calm. I wish we could be on the other side already. There are moments when I feel worried and desperate... in the name of Jesus, I pray that this ends soon. It has not been easy. The roads we have walked down, we have suffered. I have seen women badly beaten on the street and left behind to their fate. Then, with Johnathan's health scares, we've had so many horrible experiences along the way. It’s been rough, to be neither here nor there. Back in Honduras, I suffered domestic violence, and my two eldest daughters were sexually abused, and I don't want my two little girls to go through the same nightmare. I want a future for my children. They all three love football, and Johnathan loves to play the drums. You see, my children have dreams of their own, and I wish to get to a place where they can develop those dreams, those dreams of their own, and to be someone in the future. I want to work and put my kids in school where they can learn many things. I would like them to learn to paint. I think they would like that very much. That is my dream, and I pray God will give me the wisdom to show me the way to the other side. But now, I do not know where to turn, where to search for refuge. In a simple truth... I am between a sword and a wall.”

φ

Poems I Brought Down From the Mountain

Liminal Health: The Maya of the Guatemalan Highlands

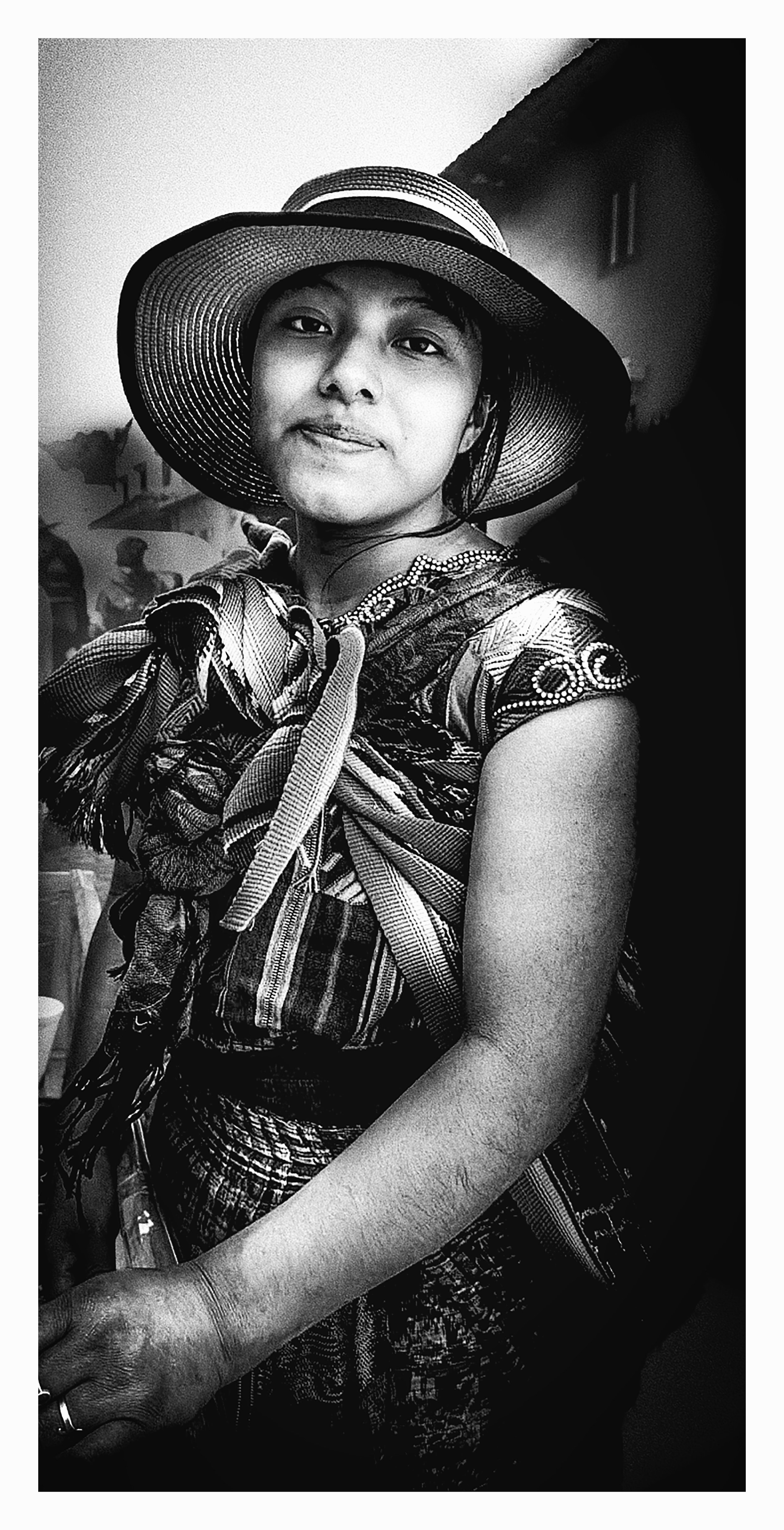

As an artist, I am deeply committed to using my work as a means of bearing witness and fostering understanding of unknown peoples and places. My most meaningful documentary work has brought me into the heart of the Guatemalan highlands, where I have dedicated myself to telling the stories of the Maya people. Their resilience in the face of historical injustice—especially the legacy of civil conflict, much of it exacerbated by outside intervention—has left a profound impact on me. Through my lens, I strive to honor their dignity and shed light on both the ongoing discrimination and the acts of genocide they have endured. However, I hope that my work will do more than simply inform; I wish for it to inspire action. I believe in the power of storytelling to open hearts and create a more empathetic, aware, and responsive audience. Ultimately, my goal is to honor Maya culture, amplify their voices, and encourage others to join in the pursuit of justice and positive, sustainable change for the Maya and all marginalized communities. This journey is both personal and collective—a call to see, to feel, and to act.

In February of 2019, I traveled to the highlands of Guatemala to observe and document those causes of migration and the ongoing efforts to improve living conditions in a specifically troubled region of the Northern Triangle, known as the “Altos.” Through my work with the NGO Feed the Children, based in Guatemala City, I gained insight into the severity of food insecurity and the devastating effects of malnutrition on child development, as well as their dedication to fighting hunger and creating better futures for Maya children and families.

I collaborated with ASSADE, an organization founded by a remarkable woman who survived the genocide, even though her brother, who worked alongside her providing healthcare to the Maya during the war, was killed by the Guatemalan army. In his memory, and with unwavering courage, she continued their mission, establishing ASSADE in the highlands to deliver vital healthcare to the Maya in remote areas, as well as through their clinic in San Andrés Itzapa. Additionally, my journey led me to Priméros Pasos, whose dedicated staff operate a clinic in Xela and extend their services to distant Maya villages.

In the mist-shrouded highlands of Guatemala, the Maya have lived for centuries, with their traditions and language echoing across mountains and valleys. As descendants of one of the world’s great ancient civilizations, the Maya of Guatemala have endured long before the Spanish arrived in the 16th century. They thrived in these lands, building cities, cultivating maize, and charting the stars. Colonization, however, caused disruption—land dispossession, forced labor, and the imposition of foreign rule. Still, the Maya survived, adapting their lives and customs, preserving their languages, and weaving their history into vibrant textiles, rituals, and stories.

But the 20th century brought new challenges. As Guatemala modernized, the Maya remained largely excluded from political and economic power. Tensions over land, inequality, and identity simmered until they erupted into civil war in 1960—a conflict that would last 36 years. During the darkest of times, the Maya suffered immensely. The Guatemalan military, driven by fear and prejudice, targeted Maya communities in a campaign of violence now recognized as genocide. Villages were razed, families shattered, and one to two hundred thousand Maya lost their lives or were displaced (though some claim the death toll could be in the millions).

Yet, in the aftermath of war, the Maya endured, though the decades since the signing of the peace agreement in 1996 have brought new challenges—poverty, discrimination, and the pursuit of justice—but also resilience, revival, and hope. Across the highlands, Maya communities continue to honor their ancestors, celebrate their languages, and assert their rights. Their lives today are marked by both continuity and change: ancient rituals coexist with cell phones, traditional dress with modern education, and old wounds with new dreams.

To this day, both NGOs continue to provide comprehensive healthcare through a participatory model, alongside their ongoing efforts to ensure that healthcare is not a privilege, but a right for all. This remains their everyday mission.

“Many years have passed, bringing numerous changes and challenges,” my friend Julio from ASSADE recently told me, “The pandemic was a significant milestone for both our work and our lives. It set us back... but also taught us great lessons about how everything is interconnected, which I believe is transforming us. This project represents our voices—our communities in the highlands—a work that, without it, no one would know what is happening. Speak loudly; this is why my heart is full of joy and hope for your project. Lastly, I´d like to mention that I am proud that my mother is the founder of ASSADE. When she reflects on the genocide and war, she emphasizes that this is how one can turn a tragic event, our grief, into something beautiful and healing. This is our struggle; this is our mission.”

Early each morning, while working in Guatemala, I would find a local cathedral to sit and meditate on my experiences in the country. I had witnessed so much suffering along my journey, from the migrant camps in Mexico to Guatemalan villages, where more children than not had severe brain underdevelopment due to malnutrition. Their faces were covered in scars, and their noses bloodied by the rugged realities of growing up in mountain-top villages, where their families had been forcibly relocated as the government, on behalf of international mining companies, pushed them further and further toward the peak. I’d try to process why women outnumbered men so greatly, as husbands and sons had migrated to the United States in search of work. Women with their own scars worked the dry, cracked earth surrounding their adobe, stick, and steel homes, desperately trying to harvest corn amid a devastating drought.

I’d begun my journey in Guatemala with Feed the Children, based in Guatemala City, which worked in villages throughout the Altos, assisting schools with meal programs, teaching parents how to cultivate gardens, and supplying seeds and tools that would yield more nutrition than maize alone. I moved on to Antigua, where I worked alongside ASSADE, based in San Andrés, which also operated remotely in convents, schools, and villages wherever they could or needed to go to provide healthcare to isolated communities.

Picked up early each morning by motorcycle. I’d ride on the back with my gear as we crossed the active volcano spewing smoke and ash into the dawn sky that divides Antigua and San Andrés Itzapa¾the magnetic field of the mountain strong enough to pull on the gears of a watch, slowing time, as we’d arrive from one world into another, one more ancient, more isolated, more preserved, yet more vulnerable. As the clinic did not open until 9, though families would already be lined up down the block awaiting care, I would walk to the Iglesia San Andrés church a few blocks away. At that early hour, the pews remained silent, minus the clogs of nuns whisking away on early morning chores. Amidst the land's strong energy and the sanctuary's peace, I’d sit and try to heal, often writing down my thoughts and reflections.

“I am drawn to these places where the world is still real,” I wrote, “where I can feel the past, the connection between things, and the course of events that led to this point; where I can look back and see the journey I’ve traveled—a path that can't be quickly paved over with denial or disillusionment.”

Upon arriving at the last home in the mountaintop village we’d visit that day, I exchanged glances of gratitude with an entire family living in little more than a cattle shed. Despite enduring genocide, displacement, and unimaginable discrimination, resilience thrived upon dirt floors. The Maya of the Guatemalan Highlands communicate through the eyes, revealing unspoken truths hidden within.

After taking a dozen or so portraits, we’d gather by a crackling horno, sharing a stack of hand-slapped tortillas and a half-dozen hard-boiled eggs. I yearned to immerse myself in such simplicity, yet I knew I must eventually leave the warmth and step outside into the fog and haze, feeling the weight of an ancient legacy bearing down upon me.

Descending the mountain, I’d spotted a puma’s kill cached in a lone cacao tree and heard a rustle and turned back to see a girl with gleaming gold teeth within a broad smile step out of the corn stalk. She seemed to yearn to be seen, as if disappearing from sight was akin to death. Raising my camera, I worried her weary eyes might be seen through a lens of pity as she waved me goodbye, a fading silhouette against a backdrop of mist, and a dream as clear as day.

Halfway down the mountain, Julio from ASSADE told me he wanted me to meet someone special, a 17-year-old girl named Yeny. As I sat down with her outside her family’s humble home for an interview, she told me she was only 13 when she started going door-to-door in her small highland village to teach children how to brush their teeth. Recently, she has been providing fluoride treatments, handing out toothbrushes, and teaching children how to brush with a comical pair of false teeth that drew laughter from the kids. She has a box in her family's home with a bottle of aspirin that she distributes to people who show up at her door in pain. Her dream is to be a doctor, and a few days a week, she walks a long trail to the village at the base of the mountain, where she studies medicine. If all goes according to plan, she will graduate this summer with a degree in nursing and be permitted to administer medicine to her village. Although her box currently contains only aspirin, she hopes to receive donated medicines from a local NGO.

Yeny, still a child but already a leader in her community, makes her mother proud. When I ask her how she felt about Yeny's unique ambition to help the people of her village, she smiles broadly as she warms a tall stack of tortillas over the wood stove in the family kitchen. When I ask Yeny if she is proud of herself, she does not understand the concept; she does not see herself as separate from her neighbors and expresses no pride. It is clear that Yeny is simply a human being doing what humans are meant to do: care for one another.

I collaborated with Primero’s Pasos Clinic, based in Xela, in the northwest highlands. There, we’d set out from the clinic each morning, traveling in the back of pickups and often by foot deep into the mountains, offering healthcare, visiting schools, and training villagers how to filter contaminants from their drinking water. Around easter, I was mugged and beaten in Xela by five men right outside the door of my accommodation. Though a bad concussion and three broken ribs didn’t stop me from climbing back into the mountains the next day, it did remind me of the harsh realities of a land that can easily enchant with the high-altitude light softened by the fog.

After many months in the highlands, I descended from the mountains and spent my last 60 days in the lakeside village of Panajachel. I was there to document a local effort to connect Maya women who knit textiles, specifically the woven skirts known as hulpil, with a global fair-trade market. The hulpil is a richly decorated blouse, usually featuring intricate embroidery and patterns unique to each community and region. The village was bustling with expats and tourists, and my time there served as a bridge to the outside world, which I was gradually preparing to reenter. It was on my last full day, before leaving the country, that I heard horrifying news. I immediately went down to the shore of Lake Atitlán. A beautiful young Mayan woman, who had come down from the mountains to work a summer job in Panajachel, had washed up nude on the shore for fishermen to discover.

By noon, burning candles and red roses had replaced her cold, blue body, and accusations began to spread throughout the village, surrounded by a ring of dormant volcanoes. An unholy truth would soon come to light. Her name was Silda. She was 26 years old when, hours after arriving in the village of 16,000, she was kidnapped, taken on a boat, raped, hogtied, and thrown overboard into the abyss of one of the world’s deepest lakes. While impunity is one monster, the fact that police officers were the ones accused was quite another; however, the horrors of femicide remained the same. As I stood over the flickering candles on the rocky shoreline, extinguishing one by one by the ever-changing winds, I thought about how, here in this Northern Triangle nation, just like stray dogs on the streets, the individual Mayan was not steadily recognized by the eyes of the state, leaving me to ask: In a land where being unseen is akin to death, how can you extinguish a flame that was never allowed to burn?

The words of Mayan Poet and philosopher Hunbetz Men, I quote:

“If I destroy you, I destroy myself.

If I honor you, I honor myself.”

The plan was to next travel to Honduras to document the femicide and gang violence that was driving so many people away. However, the early stages of the pandemic hit us, and we had to scrap those plans. I holed up in Mexico City, feeling just as uncertain about life, the future, or anything else. But fate and a 2024 election would bring the topic of migration back to the forefront on an unprecedented scale. The time was perfect to revive this project. I returned to Guatemala in June 2025 to work on this presentation in the Altos, as I felt that was incredibly important. I also met with Yeny again. Now six years older, she was able to share much more about her life in the highlands and how things had evolved for her.

“Guatemala is a beautiful country rich in culture,” she told me, “...with its traditions, beliefs, diverse neighborhoods, and languages.

“But it's also a country where there is poverty, malnutrition, and a lack of decent education and decent housing. This can be seen everywhere, even in the capital and cities, where governments offer better education, healthcare, and security. The government also provides aid in remote villages, but the truth remains that it has abandoned many hamlets. When the government struggles financially, individual politicians who profit from government funds to become wealthy seem to change their way of thinking. Their actions are then only for their own benefit, and year after year, no government has shown improvement.

“San Andrés Itzapa is now my town. But Panimaquin is my village; it is where I was raised. It is a place where neighbors look out for one another. If a neighbor is going through a loss, illness, or economic need, we help each other. We survive on livestock (cheeses, cottage cheese, and milk). There is a lot of agriculture. We harvest various crops, depending on the type of vegetable. The harvest (cauliflower, broccoli, peas, carrots, corn, beans, radishes, cilantro, avocado, and peach) is for consumption and is taken to distribute sales to the towns or the capital (Guatemala City). In my village, children play in the streets during the day, even in the late afternoon and evening, without fear of something happening. With a minimum interest in studying on the part of parents, children are less likely to have the opportunity, and if the family is very poor, studies are discouraged due to the lack of employment, due to the distance factor from the center, the factor of roads in poor condition, lack of transportation, and lack of a school within walking distance, which is all in all, a bad factor the economy. Also, where adequate nutrition is lacking, it's not clear what the right course of action is.

“For me, being Mayan means Guatemalan pride. I feel blessed to be Mayan and to speak the Kaqchiquel dialect. But regardless of being Mayan or of Spanish descent, there must be equality, and where there isn’t, it’s because of ignorance. Among those of Mayan descent, there are some individuals who lack knowledge about current events, their own beliefs, and the culture and respect that accompany it, partly due to isolation and a lack of opportunities. But many of us have retained a part of what it means to be Mayan. Among us Mayans, some are very high, exalting the power to be intelligent, rising from the most forgotten places, exalting Guatemala, just like those of Spanish descent. But in our society, we still see a lot of discrimination, a lack of empathy, and that's where we see ignorance. And because of this, we suffer from a lack of basic services and education.

“In my family, I have four sisters and two brothers, all of whom have a two-year age difference. When I was still a two-year-old girl, my father emigrated to the state of Texas (USA). For eight years, he worked hard to buy us a house made of blocks and sheets, and to pay off some debts he incurred to pay a so-called "coyote" who took him to Texas. My mother struggled while he was gone, being alone in Guatemala with all of us children. However, she strongly supported my father’s choice. When my father returned, he dedicated himself to farming. We all went with him to the fields, regardless of age. We helped him plant and grow crops (guacoy, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, sweet peas, and spring peas). My sisters, brothers, and I were fortunate to have been given the opportunity to study in elementary school. But when we returned from school, we would have lunch and then meet our parents in the mountains to go to work, until we would return home at 6 p.m. In rainy weather, we covered ourselves with nylon capes. My father made the capes for us. I liked going to the fields. It's very tiring and hard work, and it’s not very well paid, but I would always want to, regardless. And that’s how we grew up. My family attends the Catholic Church. Since I was little, my mother taught us the importance of attending church for the Faith and Hope that exists in the Father, our Creator, and his Son, Jesus Christ.

“Even after finishing primary school (thank God), we still feared not having the opportunity to study further for a basic education. We had to go to the national school in another village, 5 km away. That’s how the three years of basic education went. When we returned from school at 12:30 pm, we wrapped our bags in plastic bags and stayed behind to help in the fields. When we returned from the fields at night, we did our chores. In elementary school, I enjoyed taking drawing classes. I loved drawing. When I was in my final year, my classmates were asking each other what they would like to continue studying after finishing elementary school. They asked me, "What would you like?" and with a shaky voice, I answered something about drawing because I liked it. And I remembered a painter who went to school to do some paintings behind the elementary school wall. I asked her if the career she chose was very expensive, and she replied that it was. My family doesn't have many resources to pursue that dream, and my father wouldn't want me to follow it. A year passed after graduating from elementary school, and I didn't know what to continue studying. I thought about what I enjoy doing. It crossed my mind a lot, until I decided to study a bachelor’s degree in computer science and a nursing course at the same time.

“My brothers and sisters, who finished basic education much earlier than I, saw my family’s poverty and believed that my parents, who were dedicated to agriculture, could no longer support it, so they ventured out on their own. However, when I finished high school, I stayed behind to help my parents in the fields. I liked selling the vegetables my family grew at the town market. I have a friend from high school who one day told me about a job at an association in the town of San Andrés Itzapa. She took me to that place, where I met the ASSADE Association, and I was hired to provide an educational program on tooth brushing. I went around the village, visiting houses to find children applying fluoride to their teeth and brushing them properly, both adults and children. I also helped disseminate information provided by the association, seeking out the neediest families to deliver food supplies, distributing water filters to families in neighborhoods, conducting surveys, investigating the village's drinking water system, provided donations of water purifiers, as well as educational talks on their use with the participation of foreign donors, food donations, and more. We tried to do the impossible, but unfortunately, we weren't able to achieve it. However, I feel happy that I gave my all to help my village and that I had the opportunity to realize I liked helping people in various ways. That's why I continued studying to become a nurse.

“During my year of training to become a nurse, it was a considerable challenge. Classes were held Monday through Friday from 7:00 am to 4:00 pm. On weekends, I worked to support myself financially. These were days of continuous sleepless nights due to work assignments. I didn’t give up until I achieved what at times seemed difficult to accomplish, with grades of 80 to 90. Until I achieved one of my dreams. Then I began to create my resume. I visited three hospitals in my community of Chimaltenango. However, it was in the capital city, five months after graduating as a nurse, that I was called to the Guatemala City Medical Center, Zone 10. To enter, I had to undergo a lengthy process, including meetings, a polygraph test, and knowledge exams. When I was able to enter the hospital, I had to pass two months of probation, rotating shifts. It was quite a challenge, with very tiring shifts, learning new things each shift, meeting new people, new colleagues, and a new environment. But thank God I managed to pass them at the end of the two months. Then I transitioned from rotating to 24-hour shifts every three days, and I was finally issued a hospital uniform. Recently, they moved from working with bedridden patients to the Maternity Ward, where I help deliver babies and care for the mothers. The hours are long, and the commute by bus is 5 to 6 hours each way, depending on weather and traffic. However, I enjoy learning something new every day, among the diverse characters I meet and the various ways of thinking of each patient. I strive to provide the best service, regardless of the language or country from which they come. My goal is to move forward every day and pursue better opportunities. I will always dream of achieving more, just as I have done until now with effort and dedication, and to never lose faith.”

I’d listened to the stories conveyed in words and stillness and silence alike, of lives and journeys, and realities parallel and adjacent to our own. And now, I reflect on our shared responsibility as American citizens. Migration is not merely a political issue; it is a human story, written in footsteps and carried in hope for countless grueling miles. I am honored to share this story with a hope of my own: that, together, we, as Americans, can help build a world where every journey is met with dignity and compassion, regardless of our origin or the color of our skin. After all, all Americans—north, south, and central—deserve a dream. The history of immigration is not just in the past; it is an ongoing tide. And while history is littered with a cast of lawless monsters, today, as we take the stage, we must decide which characters we want to be. The time has come to ask: Will history look back upon us as monsters or as human beings who simply did what humans are meant to do: care for one another...?

φ

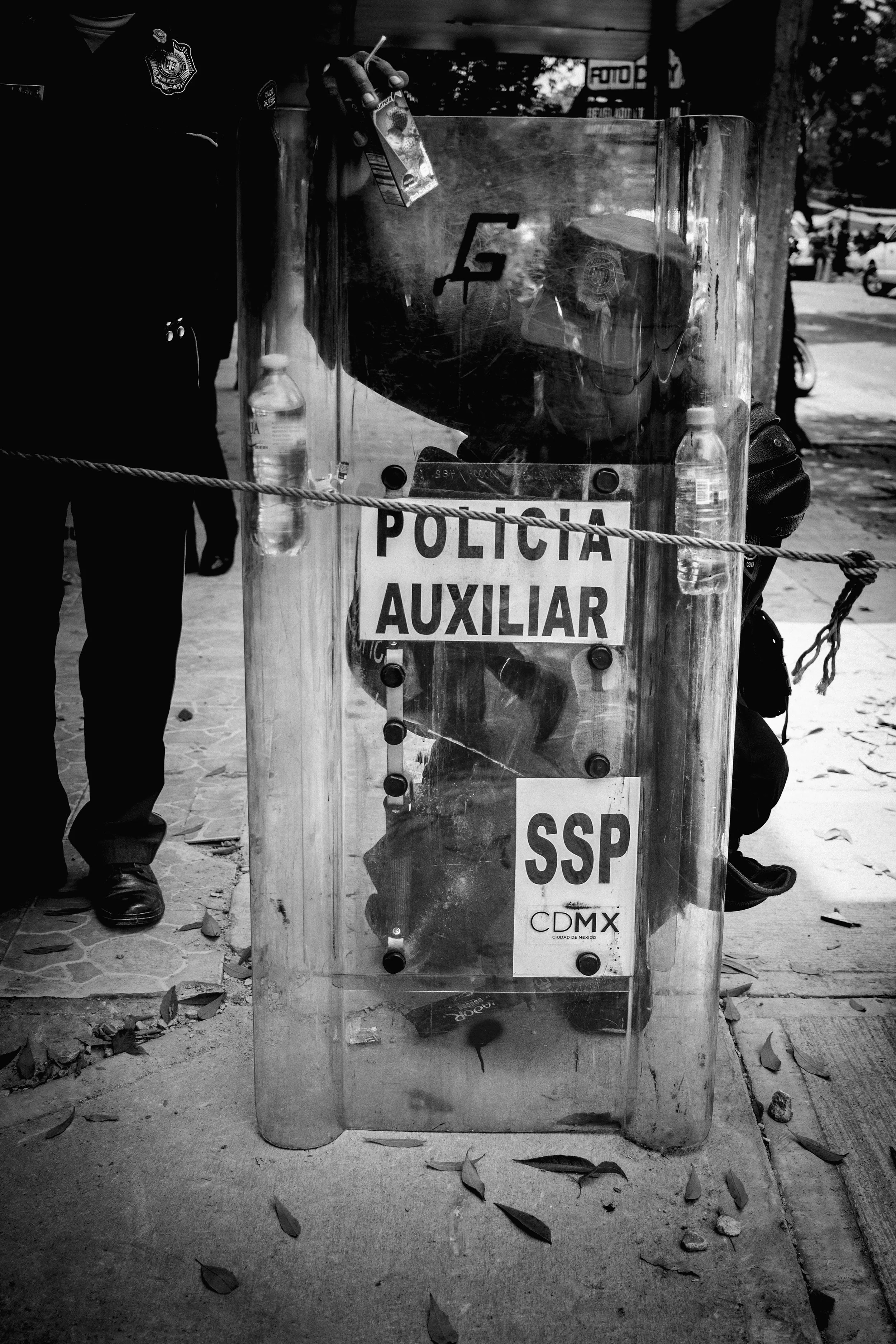

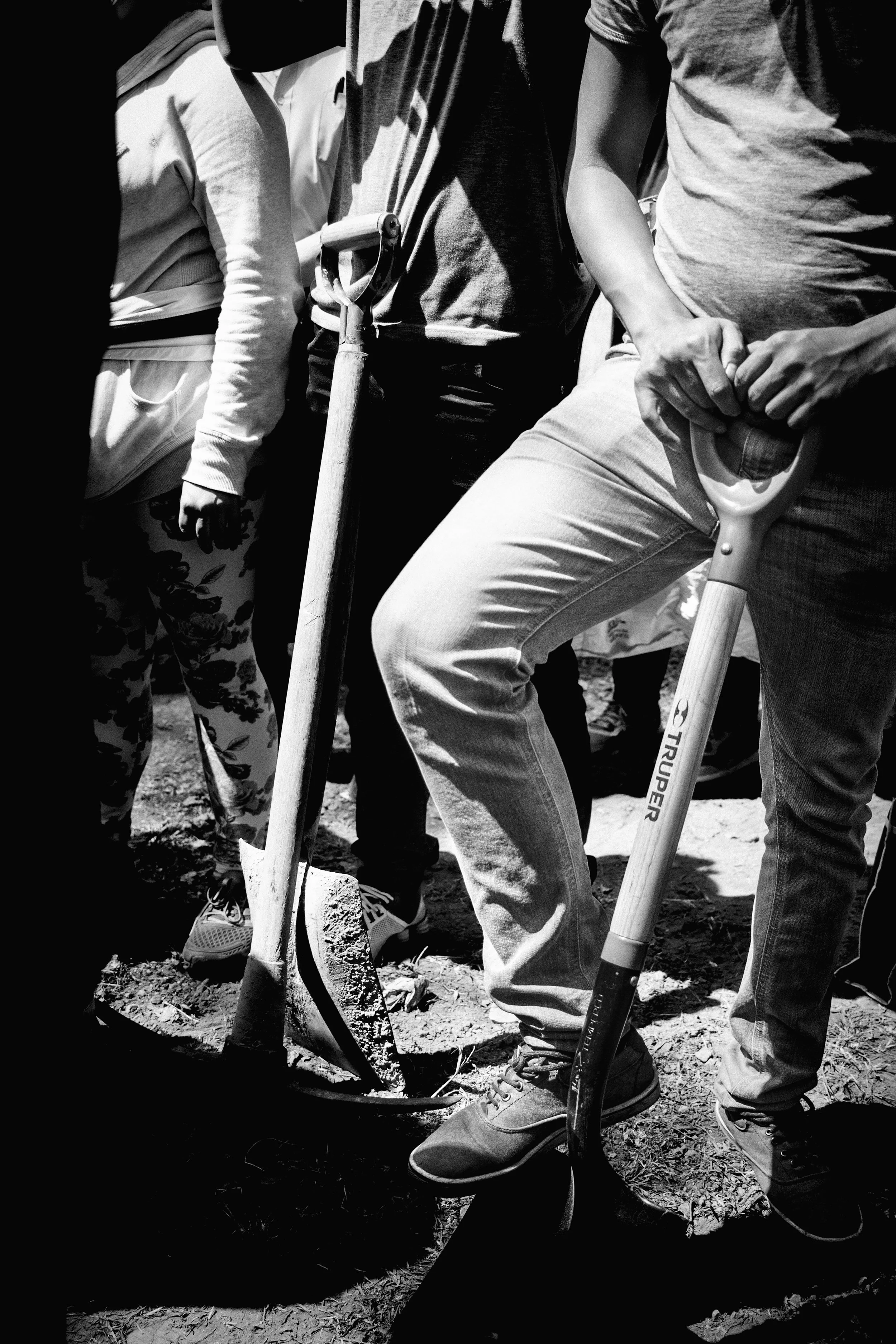

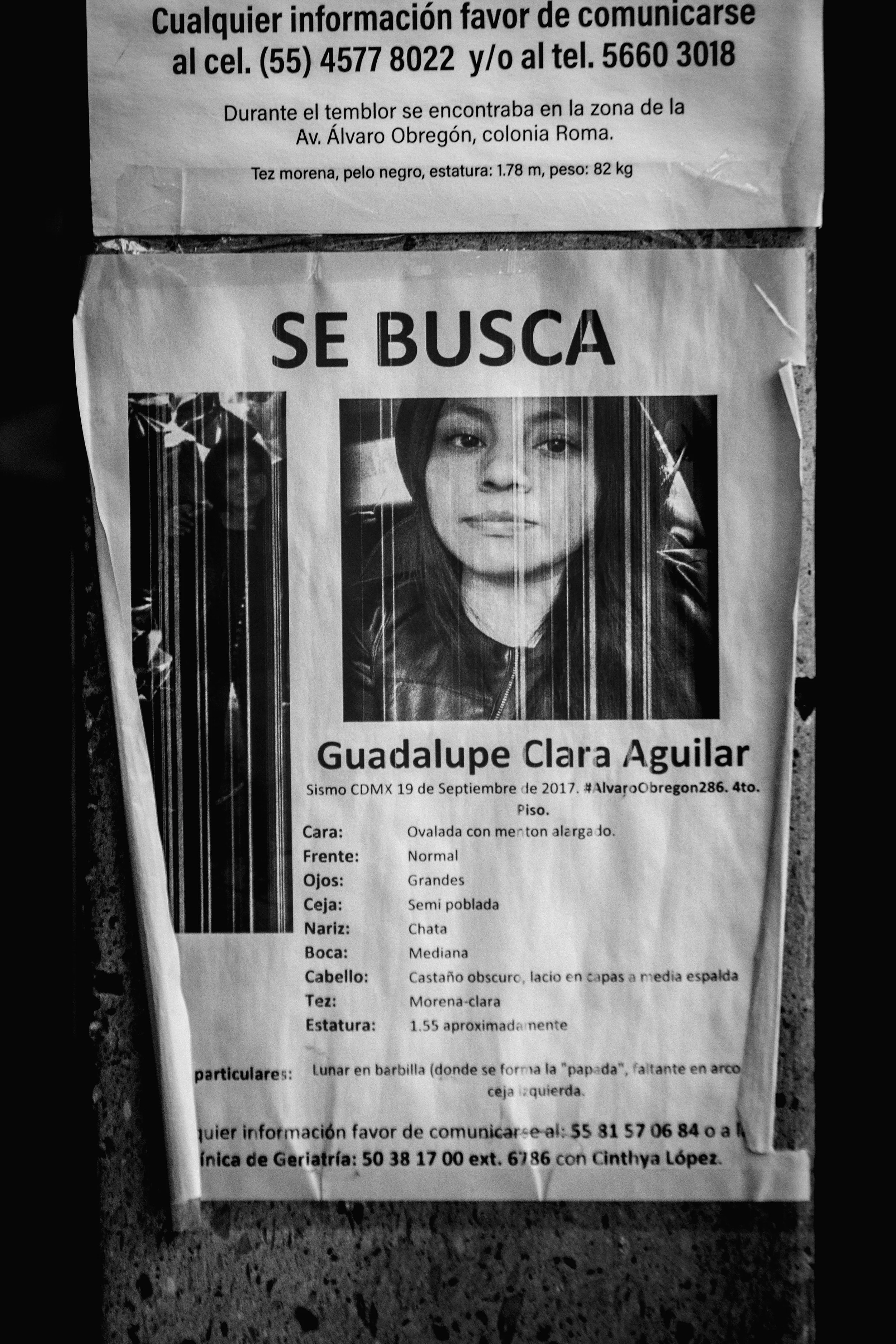

SISMO CDMX

The Mexico City Earthquake of September 2017

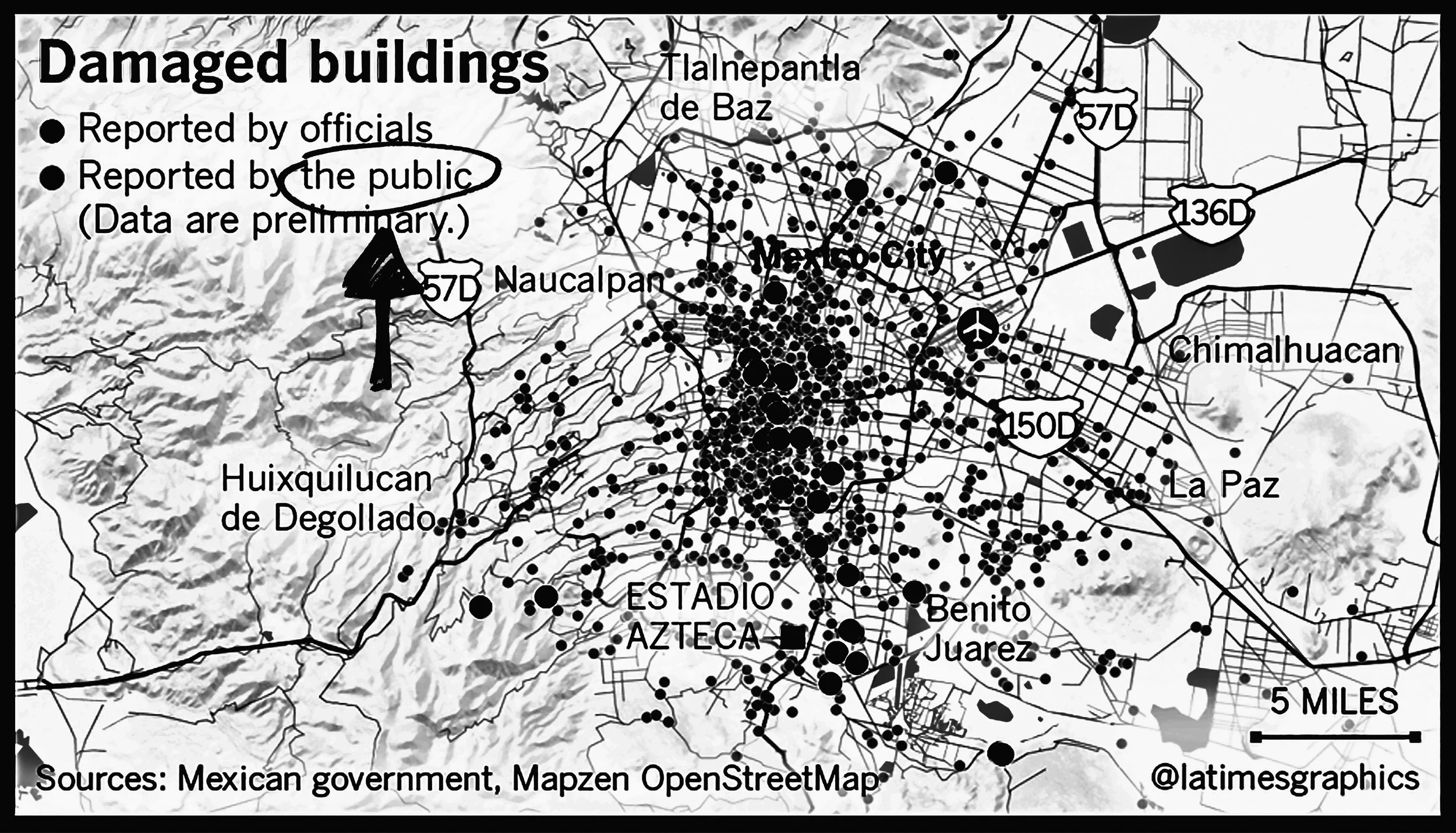

The earthquake in Mexico City was the most frightening experience of my life; there is nothing like the shaking of the earth to rouse every cell of your mind and body. As I walked the streets after fleeing my apartment, I saw people in tears, horrified not only by what they had just survived but also by memories of the last time this happened at this magnitude, 32 years prior… to the day. The thunderous force that had rewritten the cityscape had given way to a dead silence fallen flat beneath the cries of car alarms, and soon the whooping blades of swarming helicopters hovered over the immense damage. I decided not to take photos. Instead, I decided to absorb this moment into my soul. I knew I was experiencing something very deep and emotional, and I needed to maintain a state of reverence. But the following days, I went out into the streets, expecting to see pure misery on the faces of the people. And, I did see that which cannot be wiped away in a matter of hours or days as one's neighbors lay trapped under mountains of rubble. But what struck my heart and made this dynamic mix of emotions even more complex were thousands of people in the streets with hard hats, pickaxes, and shovels. Determined people, constrained only by the police and the Marines, in their attempt to do whatever it took by their own means to rescue their neighbors and loved ones. There were droves of people coming in by truck, motorcycle, and on foot, carrying food, water, and an endless train of supplies for victims and volunteers. And beyond the sadness and heartache, you could sense this rising wave of hope, unity, and pride. The people of Mexico City wanted not only to show themselves that they were proud to be Mexican, but also to show the world what being Mexican truly meant to them: being a true human being, with heart and compassion, and the will to do whatever it takes to help those in need. And for many, if not most, this was the first time in their lives they had the chance to truly transcend stereotypes and redefine who they are as a people. Solidarity, resilience, loyalty, and love were their creed, and nothing was going to stop them from rising to their highest selves and serving their community and nation, not their own government, not international politics or propaganda, not their own physical limitations, not even the Earth. I was honored to capture what I could of the soul of these proud and honorable people during a time most trying, more trying than many will ever know in their lives.

El terremoto de la Ciudad de México de septiembre de 2017

El terremoto en la Ciudad de México fue la experiencia más aterradora de mi vida; no hay nada como el temblor de la tierra para despertar cada célula de tu mente y de tu cuerpo. Mientras caminaba por las calles después de huir de mi apartamento, vi gente llorando, horrorizada no solo por lo que acababa de sobrevivir, sino también por los recuerdos de la última vez que esto sucedió con esta magnitud, 32 años antes… ese día. La fuerza atronadora que había reescrito el paisaje urbano había dado paso a un silencio sepulcral que se había derrumbado bajo los gritos de las sirenas de los autos y, pronto, las aspas de los helicópteros que sobrevolaban los inmensos daños. Decidí no tomar fotos. En cambio, decidí absorber este momento en mi alma. Sabía que estaba experimentando algo muy profundo y emotivo y que necesitaba mantener un estado de reverencia. Pero los días siguientes, salí a las calles, esperando ver pura miseria en los rostros de la gente. Y vi aquello que no se puede borrar en cuestión de horas o días mientras los vecinos yacían atrapados bajo montañas de escombros. Pero lo que me impactó el corazón e hizo que esta mezcla dinámica de emociones fuera aún más compleja fueron miles de personas en las calles con cascos, picos y palas. Personas decididas, limitadas solo por la policía y la Marina, en su intento de hacer, por sus propios medios, lo que fuera necesario para rescatar a sus vecinos y seres queridos. Había multitudes de personas que llegaban en camiones, motocicletas y a pie, llevando comida, agua y un tren interminable de suministros para las víctimas y los voluntarios. Y más allá de la tristeza y el dolor, se podía sentir esta creciente ola de esperanza, unidad y orgullo. La gente de la Ciudad de México no solo quería demostrar que estaba orgullosa de ser mexicana, sino también mostrarle al mundo lo que ser mexicano realmente significaba para ellos: ser un verdadero ser humano, con corazón y compasión, y con la voluntad de hacer lo que fuera necesario para ayudar a los necesitados. Y para muchos, si no para la mayoría, esta fue la primera vez en sus vidas que tuvieron la oportunidad de trascender verdaderamente los estereotipos y redefinir quiénes son como pueblo. La solidaridad, la resiliencia, la lealtad y el amor eran su credo, y nada iba a impedirles alcanzar su máximo potencial y servir a su comunidad y a su nación, no a su propio gobierno, ni a la política internacional ni a la propaganda, ni a sus propias limitaciones físicas, ni siquiera a la Tierra. Fue un honor para mí capturar lo que pude del alma de estas personas orgullosas y honorables durante un momento muy difícil, más difícil de lo que muchos conocerán jamás en sus vidas.

Guardian News

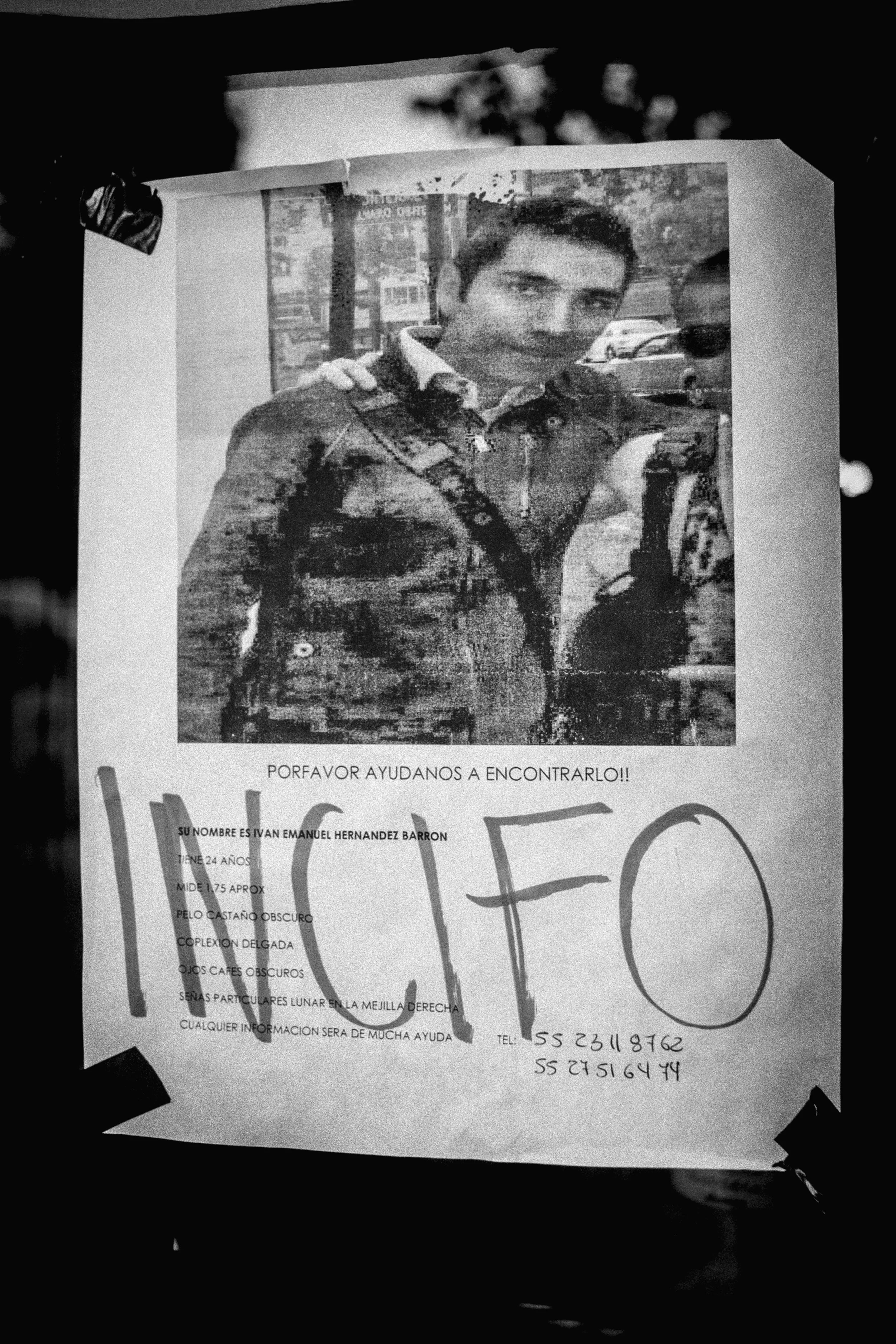

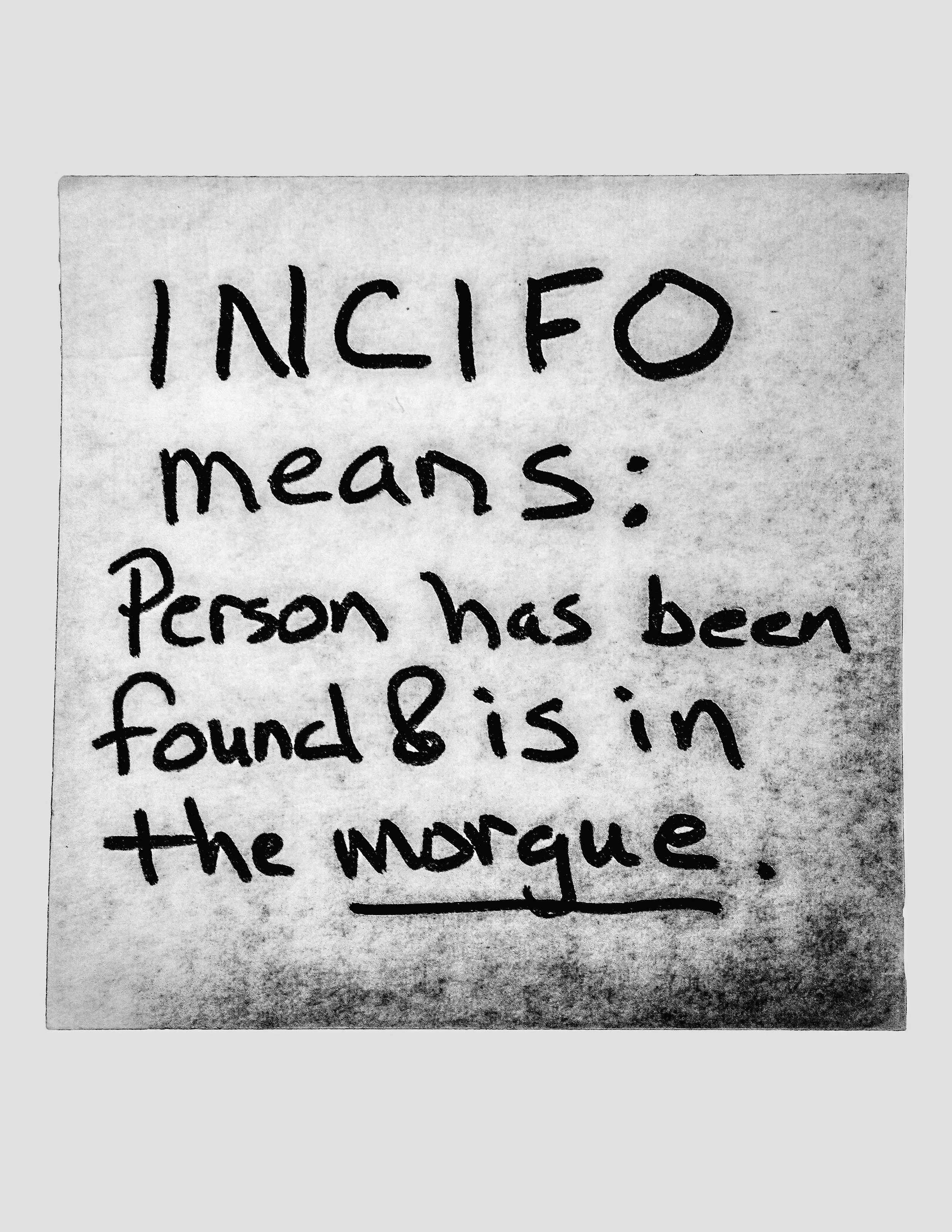

Who died and who survived the collapse remains unknown, and authorities have failed to produce a list of the companies and workers operating in the building, fueling speculation that the building housed clandestine sweatshops staffed by undocumented migrants.

And with no official missing persons register, fears are mounting that many earthquake victims will go unidentified and unclaimed, especially if they came from abroad or belonged to the capital's invisible army of informal workers who clean houses, cook street food, polish shoes, and guard buildings.

In Mexico City, 6 out of every 10 workers are employed in precarious, unregulated jobs characterized by poor conditions and negligible rights.

In the days immediately after the earthquake, Mexican authorities were repeatedly accused of attempting to clear away the rubble before rescue groups had exhausted their search for survivors.

During the recovery efforts, Mexico witnessed an outpouring of civic sentiment, with legions of volunteers spontaneously organizing themselves to help with rescue efforts and tend to survivors.

But the country's rigid class divisions were also on show. The Mexico City daily El Universal ran a photo spread in its social pages highlighting the socialites and celebrities who joined in the clean-up operation.

"Domestic workers are invisible: many employers don't know the surname of the person who works in their home, or where she comes from," said Marcelina Bautista, founder of the centre for support and training for domestic workers (CACEH).

Since the quake, some domestic workers have been fired without receiving outstanding pay, according to Bautista.

Of the 250,000 working in the capital, 99 per cent have no formal contract and therefore have little access to benefits such as health care, sick pay, and redundancy compensation.

"With no register of domestic workers, they can easily be ignored. If they didn't exist before, they certainly won't when it comes to compensation."

Noticias del Guardian

Se desconoce quiénes murieron y quiénes sobrevivieron al derrumbe, y las autoridades no han publicado una lista de las empresas y los trabajadores que operaban en el edificio, lo que alimenta la especulación de que albergaba talleres clandestinos de explotación laboral atendidos por migrantes indocumentados.

Y sin un registro oficial de personas desaparecidas, crece el temor de que muchas víctimas del terremoto queden sin identificar ni reclamar, especialmente si provenían del extranjero o pertenecían al ejército invisible de trabajadores informales de la capital que limpian casas, cocinan comida callejera, lustran zapatos y vigilan edificios.

En la Ciudad de México, 6 de cada 10 trabajadores tienen empleos precarios y no regulados, caracterizados por malas condiciones y derechos inexistentes.

En los días posteriores al terremoto, las autoridades mexicanas fueron acusadas repetidamente de intentar retirar los escombros antes de que los equipos de rescate hubieran agotado la búsqueda de sobrevivientes.

Durante las labores de recuperación, México fue testigo de una efusión de sentimiento cívico, con legiones de voluntarios que se organizaron espontáneamente para ayudar en las labores de rescate y atender a los sobrevivientes.

Pero las rígidas divisiones de clase del país también quedaron en evidencia. El diario El Universal de Ciudad de México publicó un reportaje fotográfico en sus redes sociales destacando a las celebridades y figuras públicas que se unieron a la operación de limpieza.

"Las trabajadoras del hogar son invisibles: muchos empleadores desconocen el apellido de la persona que trabaja en su casa ni su origen", declaró Marcelina Bautista, fundadora del Centro de Apoyo y Capacitación para Trabajadoras del Hogar (CACEH).

Desde el terremoto, algunas trabajadoras del hogar han sido despedidas sin recibir el salario pendiente, según Bautista.

De las 250,000 personas que trabajan en la capital, el 99% no tiene contrato formal y, por lo tanto, tiene poco acceso a prestaciones como atención médica, baja por enfermedad e indemnización por despido.

"Sin un registro de trabajadoras del hogar, es fácil ignorarlas. Si no existían antes, sin duda no existirán en cuanto a la compensación".

φ